The evolution of public relations and psychoanalysis

Series: The history of modern technical propaganda

25th of February, 2024

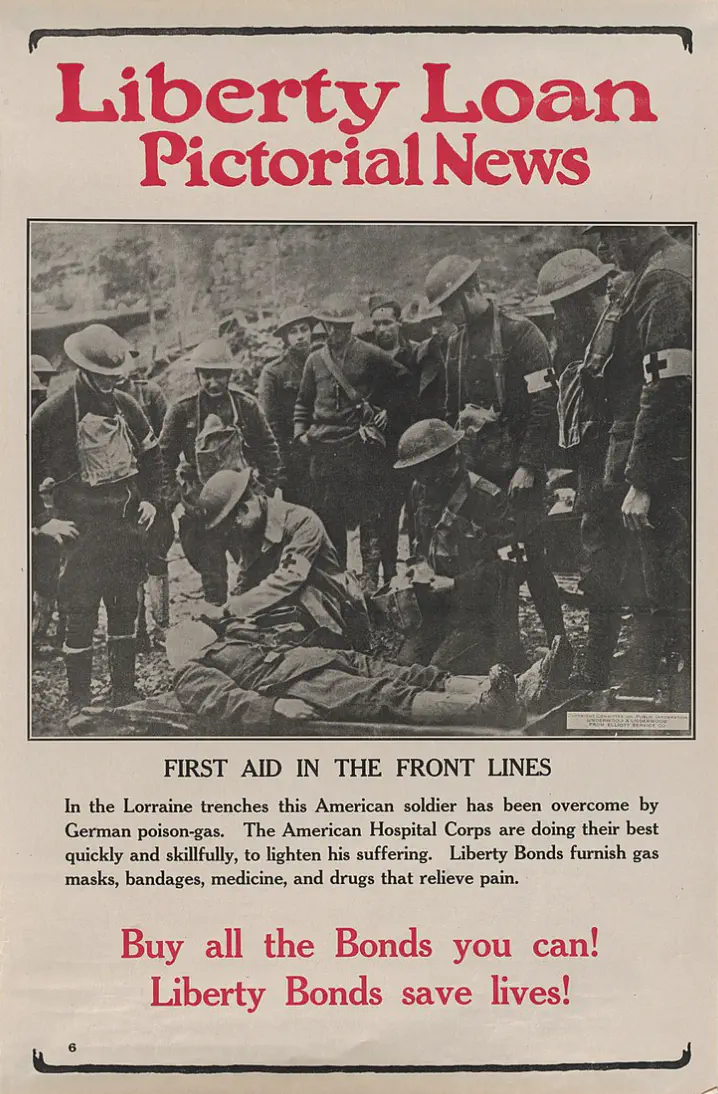

In the early 20th century, as the term “propaganda” was beginning to enter contemporary dictionaries, the United States government found itself in a pivotal moment of history. With the outbreak of World War I, the US faced the challenge of mobilizing public support for a war it had first been reluctant to join.

To help face this challenge, in 1917 US President Woodrow Wilson established the Committee on Public Information (CPI). This new department’s mission was twofold: to bolster general public support for America’s involvement in the war, and to market war bonds to help fund the war effort. The CPI employed a wide range of strategies to achieve its goals. It distributed pamphlets, produced posters, but most importantly exerted significant influence over news reporting. Their strategy was to create a “unified national perspective” that was supportive of the war effort.

However, the methods used by the CPI began to change public perception of the term “propaganda.” Initially seen as a neutral term for “the propagation of a system or a doctrine,” the term gradually took on a more negative connotation. This shift was largely due to post-war revelations about the extent of the CPIs manipulation of public opinion.

The CPIs work was “a relentless campaign of manipulation of public opinion thinly disguised as journalism.” – Chris Hedges 1

A hallmark of this “new” propaganda – and the CPIs technique – was based around the concept of “engineering consent” in democratic societies. This concept, detailed in Edward Bernays’ book Propaganda (1928), emphasizes the use of mass communication, psychological manipulation, and symbolic actions to sway public opinion to promote specific agendas or products. It essentially aims to guide the choices of society without its conscious knowledge. The contrary and ethical approach to gaining public support is “informed consent”, which emphasized transparency, truthfulness, and the respect for the public’s right to understand the facts. We can see these two approaches play out over and over again throughout history in the neverending battle for influence, from the electrical current wars to the work of the CPI.2

Let’s compare and contrast the history, styles, and influence of two central figures of the CPI, and arguably the two most important men you may never have heard of: Edward Bernays and Ivy Lee.

Understanding the work of Bernays and Lee will help us to understand public relations and marketing through a modern lens. We can trace back many marketing techniques we see today, from the press release, to the modern tech product launch, to common tropes in thought leadership (“9 out of 10 dentists agree…”), back to the works of Bernays and Lee.

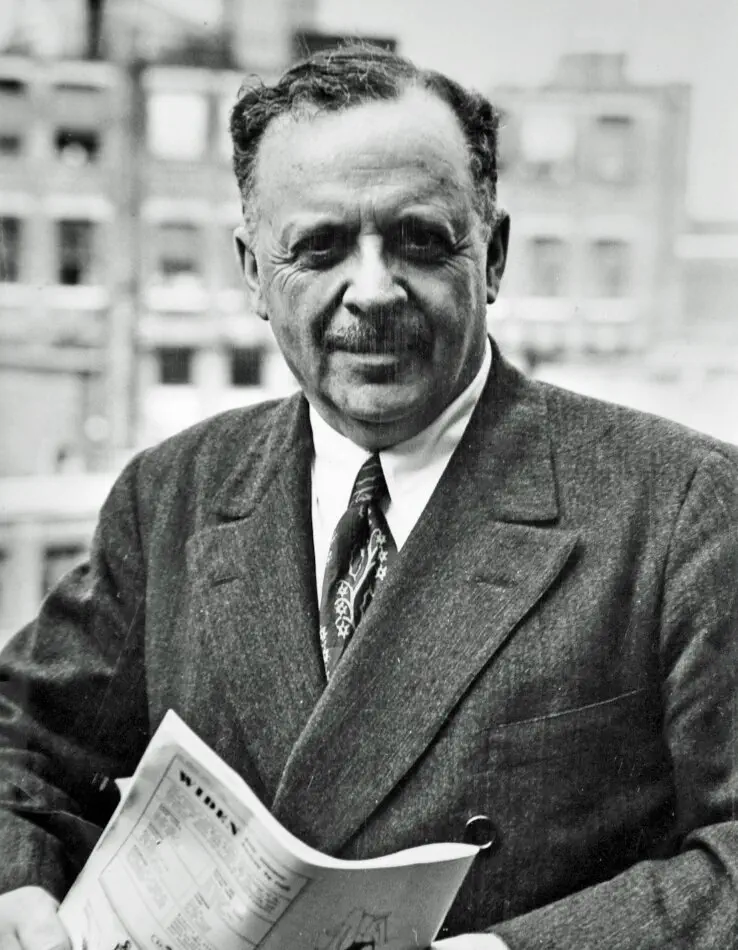

Edward Bernays

Edward Bernays graduated from Cornell with a degree in Agriculture, but abruptly shifted his career to journalism after graduating. His early promotional work – while not glamorous – gave him a solid real-world background in the realities of influencing public opinion. Notably, while an editor at the Medical Review of Reviews in New York City, he learned of an actor attempting to fund a new play on the dangers of venereal diseases. Bernays set up a “Sociological Fund Committee” to help finance the play, and enlisted so many a-list supporters that censors were unable to block its theatrical release. This early journalism and promotional work boosted his reputation and helped him to land a spot with the CPI. He leaned directly on his real-world journalism and entertainment industry experience during his time with the CPI, which included new ideas like “persuading musicians to include positive songs about military service in their repertoire and enlisting companies to distribute literature about U.S. war aims abroad”.3

Following his work with the CPI, Bernays established the first marketing consulting firm in the US, and went on to write Crystallizing Public Opinion (1923), the first academic textbook on the discipline and study of public relations. He solidified his impact on PR by teaching the first public relations course at New York University (NYU) in 1923. He later went on to author the seminal book Propaganda (1928), which was informed by a number of influences and experiences, especially his work with the CPI.4

Bernays brought a unique approach to public relations and marketing, combining psychological insights with sociology to shift the approach from straightforward advertising to a nuanced and unapologetically manipulative method of influencing public behavior. Bernays is the nephew of Sigmund Freud, who deeply influenced his views on the importance of psychoanalysis in the fields of marketing and public relations, leading to a radically unique style.

“Modern propaganda is a consistent, enduring effort to create or shape events to influence the relations of the public to an enterprise, idea, or group.” – Edward Bernays

Ivy Lee

Ivy Lee transitioned from journalism to PR in the early 1900s, and founded the earliest known PR firm in 1906. He went on to become the first public relations executive in corporate history with the Pennsylvania Railroad Company. He played a crucial role in shaping the position of what a VP-level corporate public relations executive is, and this early vision continues to this very day. Like Bernays, Ivy Lee also worked with the CPI, which is where their stories overlap. He served as a publicity director and assistant to the chairman of the Red Cross during World War I.

“Since crowds do not reason, they can only be organized and stimulated through symbols and phrases.” – Ivy Lee, quoted in American Media History 5

Both Bernays and Lee significantly influenced academia and business practices. While Bernays institutionalized public relations in academic circles through his teachings at New York University, Lee established foundational practices in the industry, such as the creation of the first press release, and created the concept of the “public relations counsel”.

A contrast of styles

While both men innovated in the same domain, their approaches and ethos differed remarkably.

Lee’s approach to public relations emphasized transparency and accuracy in communications. His practices raised the standards of corporate communications, which at the time were commonly secretive and untrustworthy, still echoing of carnival tent snake oil salesmen of the previous century.

This contrasted sharply with Bernays’ approach. Where Lee aimed for accuracy and precision in communications, Bernays was deeply influenced by Freudian psychology, focusing on the manipulation of public opinion by tapping into unconscious desires.6

In the early 20th century, Edwards Bernays and Ivy Lee, in spite of their differing ethos and methodologies, emerged as the architects of modern marketing and public relations as we know it today. Their combined legacies paved the way for the dynamic and psychologically nuanced field of marketing and the emergence of modern consumerism.

How did Freudian psychology make its way so deeply into the fields of public relations and marketing?

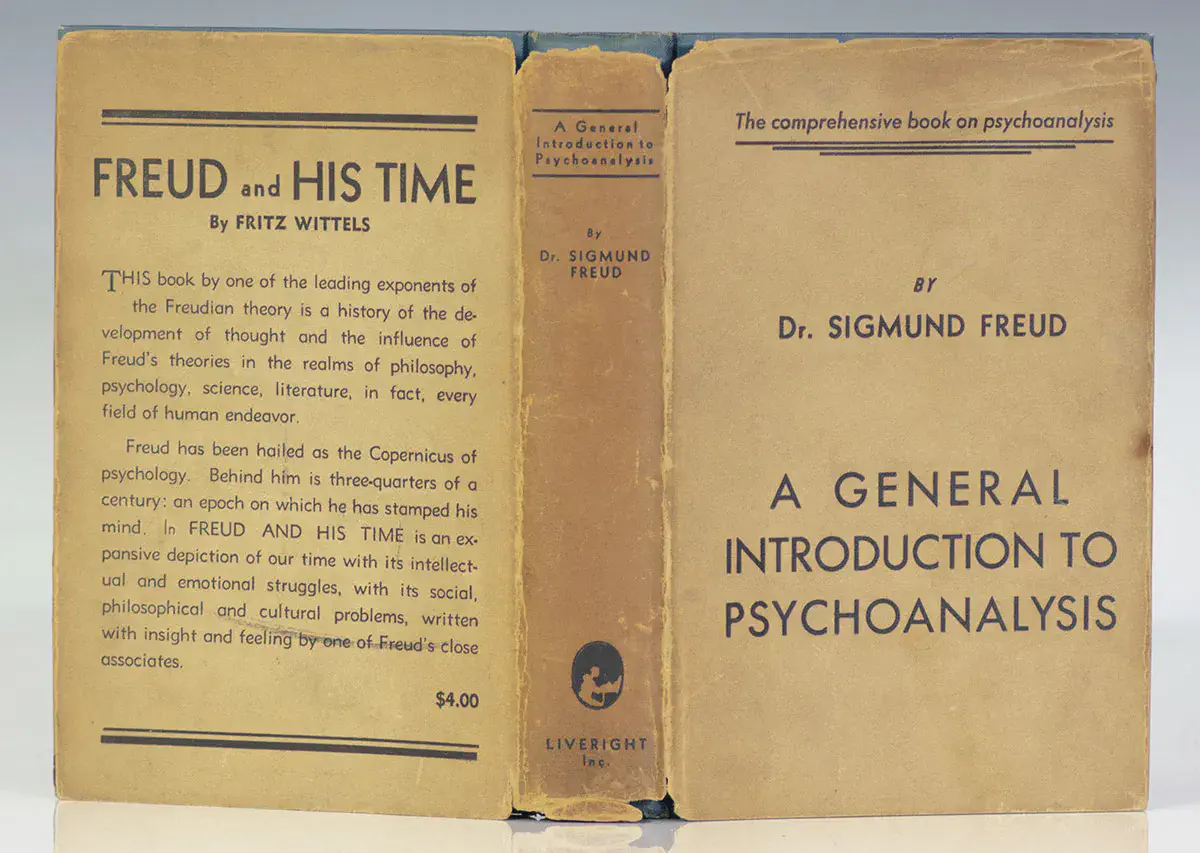

In the early 1900s, Edward Bernays direct correspondence with his uncle Sigmund Freud coincided with the creation of Freud’s most significant works. In a notable gesture of intellectual exchange, Freud personally sent Bernays a copy of “General Introduction to Psychoanalysis,” a key text encapsulating Freud’s new and innovative psychoanalytic theories refined over a series of lectures. This personal and intellectual connection between Freud and Bernays was instrumental in shaping Bernays’ innovative approach to public relations, which began to integrate deep psychological insights into the fabric of public relations and marketing strategies. Bernays began to understand that you don’t sell a product, you sell a lifestyle, and the products which fit that lifestyle will eventually sell.7

Under the influence of his uncle Sigmund Freud’s theories, Edward Bernays began to shift the focus of marketing from promoting the factual attributes of products to engineering the emotional responses they could elicit. Freud’s research in psychoanalysis provided Bernays with insights into the subconscious motivations of consumers, revealing that purchasing decisions were often based on emotion rather than rational assessment.

“What are the true reasons why the purchaser is planning to spend his money on a new car instead of a piano? Because he has decided that he wants the commodity called locomotion more than he wants the commodity called music? Not altogether. He buys a car, because it is at the moment the group custom to buy cars. The modern propagandist therefore sets to work to create circumstances which will modify that custom.” – Edward Bernays

Bernays growing understanding of psychoanalysis led him to develop marketing strategies that transformed mere wants into perceived needs, effectively manipulating consumers into buying products that they might not have needed, but desired due to the subconscious appeals created through Freudian-influenced techniques. You don’t want a luxury watch, you need one because any successful consultant must exude success and style when meeting with clients. You don’t want an agile planning tool, you need one because best practices require that teams become agile, and therefore you will need an agile planning tool.

Bernays famously stated in his book Propaganda (1928), “whatever of social importance is done today, whether in politics, finance, manufacture, agriculture, charity, education, or other fields, must be done with the help of propaganda. Propaganda is the executive arm of the invisible government.”

This encapsulates his approach to public relations and marketing as tools for molding public opinion and behavior. By applying Freud’s theories, Bernays was able to craft messages that deeply resonated with the public’s underlying desires and fears, turning the art of persuasion into a science of emotional manipulation.

True believers and rational manipulators

In Bernays’ conceptualization of propaganda, he draws a clear distinction between two types of propagandists.

On one hand, there are the “true believers,” individuals who are completely convinced by and committed to the messages they spread. On the other hand, stand the “rational manipulators,” who are not necessarily persuaded by the ideologies or products they promote, but see the strategic value in them to achieve an objective. These rational manipulators apply sophisticated marketing methods, grounded in the principles of psychology, to advance corporate interests. When the two work together to change circumstances to allow the modification of established customs, a new market is made. Coincidentally, first-movers have products ready to be sold to the new market.

In this vision of propaganda, rational manipulators skillfully construct campaigns, and then employ true believers as messengers. This tactic ensures that the message is conveyed with genuine conviction, making it more persuasive. By utilizing the authenticity of true believers to endorse products or ideas – be it cigarettes, non-stick cookware, or household appliances – rational manipulators can effectively alter public opinion through true believers as the vessel. This strategy is not just about selling a product; it’s about embedding that product within the principles and values of consumers, thereby fulfilling the company’s goals while simultaneously growing the market for their products.

Bernays’ legacy, deeply intertwined with Freud’s influence, not only changed the tactics of marketing, but fundamentally altered the understanding of what drives consumer behavior – from a model of need-based consumption, to one driven by desire through psychological manipulation.

Case study: Lucky Strikes “torches of freedom”

One of the most notable marketing campaigns of the early 20th century was engineered by Bernays for Lucky Strike cigarettes. This campaign skillfully manipulated public perceptions to break the social taboo against women smoking in public. Bernays rebranded cigarettes as “torches of freedom,” symbolically linking them to the women’s rights movement. This rebranding was highlighted during a staged event in New York City – a “smoke in” protest – where women were seen publicly smoking Lucky Strike cigarettes, ostensibly as an act of defiance and a statement for women’s rights.

However, the campaign was based on a fabricated controversy. There was no widespread societal outrage over women smoking in public at the time. Bernays cleverly manufactured this “issue” to position Lucky Strike as a champion of women’s liberation. The “protestors” at the event were actually paid actors, and the cigarettes they smoked were provided for free by Lucky Strike, a fact not disclosed to the public. This campaign was a classic implementation of his powerful propaganda concept of “engineering consent”.

The impact of the Lucky Strikes campaign was significant:

- Cigarettes, particularly Lucky Strike, became even more socially acceptable and fashionable, especially among women.

- The campaign contributed to an increase in smoking among women, as it tied cigarette smoking to modern feminist ideals.

- Lucky Strike established itself as a progressive and fashionable brand, particularly appealing to socially conscious consumers.

- This campaign is a classic example of the deceptive practices prevalent in early marketing and propaganda. It demonstrated how public relations could be used not just to inform or persuade but to actively manipulate public opinion.

“I hope that we have started something and that these torches of freedom, with no particular brand favored, will smash the discriminatory taboo on cigarettes for women and that our sex will go on breaking down all discriminations.” – A communique issued by Bertha Hunt in 1929 – a paid actor – after the staged protest

Edward Bernays – the mastermind behind this campaign – leveraged his understanding of psychology and psychological principles when crafting and executing this groundbreaking campaign. However, the ethical implications of such manipulative tactics in public relations have come under significant scrutiny, and are no longer so overt.

The duality of emotion and logic

At the heart of modern propaganda is the understanding that rational people often base decisions on emotions rather than logic, a concept that rational manipulators exploit. This principle is pivotal in various professions, and is a topic explored by Chris Voss in his book, “Never Split the Difference”.

The objective in negotiation, as per Chris Voss, is to “bend your counterpart’s reality,” not simply rely on facts. This begins with either genuine empathy or its semblance, achieved through an “accusation audit” where you validate the other party’s biggest fears as completely rational. By intensifying their emotional anticipation of loss, you leverage their loss aversion, making them more eager to seize any and all opportunities to avoid this worst case scenario. In other words, stoke someone’s deepest fears first, and then the actual request or proposal you deliver will seem only mildly suboptimal by comparison. When the negotiator pulls this off, and then presents an acceptable solution, the negotation will succeed. The other party will feel like they made the only logical decision, even though it was based on emotion.8

In the act of hostage negotiation, the agenda is noble, so emotional manipulation is fair ethical game: lives are at stake. In the corporate world, the motives of a rational manipulator are seldom noble.

Picture a situation where a leader instills an intense fear of failure and loss in an executive, which kicks off an all-consuming obsession to avoid it. The manipulator’s goal is clear: fabricate a crisis that only they can resolve, even if it’s entirely an illusion. The art of creating such crises is stunning to behold, and definitely not an easy skill to master. As the resolution to this artificial crisis unfolds, the executive team’s strength diminishes, empowering the manipulator. Even if a crushingly-slow internal hostile takeover diminishes an organization, the manipulator triumphs: controlling a weakened entity is preferable to being subordinate in a robust one. Sadly, this type of campaign is all too common in the corporate world, and probably results in more companies dying off than we realize.

The influence of Bernays, Lee, and Freud is all around us in a modern context, informing everything from public relations campaigns to corporate negotiations. I don’t share these ideas to validate the worst of these concepts, or make bold claims that “all marketing is manipulation”. Far from it. As we’ve leaned through the electrical current wars and the contrast in styles between Bernays and Lee, there is always a choice between influencing opinion through informed consent and engineered consent. By recognizing this, I hope that we can index more heavily on the most positive techniques when attempting to influence the ideas and decisions of others.

Continue reading

In the world of technology, propaganda is not just a historical concept, but a very present reality. In the upcoming chapter, we’ll weave together the historical threads of propaganda, public relations, and psychoanalysis, bringing them into the context of contemporary tech propaganda. Let’s delve into a modern example of tech propaganda called benchmarketing.

Next (part 6 of 7): Benchmarketing and The Texas Sharpshooter