Understanding propaganda in today's technology landscape

Series: The history of modern technical propaganda

25th of February, 2024

Competition in the modern tech industry is a battle for influence as much as it is a battle for technical supremacy. The term “propaganda” comes with such a visceral and negative emotional reaction that many people will be offended by its usage at first sight, but propaganda is literally the study of influence. The term dates back over 400 years, and its evolution impacts every facet of our lives. I hope that you keep an open enough mind to explore its historical origins with me and its applications in a modern business context.

The term “propaganda” is a chameleon, meaning something different to each person who comes across it depending on their life experiences. Here is the definition we will explore in this series, and how it manifests itself in a modern context:

- Propaganda is an unethical and manipulative tactic used to sway public opinion to favor the interests of certain individuals or groups.

- Conversely, education is a noble endeavor aimed at sharing knowledge, facts, and skills transparently and ethically from one individual or group to another.

- While propaganda can sometimes cross legal boundaries and become a criminal act, not all forms of propaganda are illegal, and most propaganda is never criminal.

- Propaganda always masquerades itself as education, blurring the lines between indoctrination and instruction.

The core point of this series is that propaganda masks itself as education to influence public opinion for the benefit of a small group. That’s why propaganda is alive and well in the modern technology landscape, and in my opinion, only becoming more bold.

Some of the early propagandists of World War I are the same men who founded the first marketing firms and public relations teams, and taught these concepts at a University level over 100 years ago. Limiting our usage of the term “propaganda” to only to wartime or government contexts – and pretending like it doesn’t exist in business – eliminates discussing its continuing profound and complete impact.

A classic example of business propaganda is illustrated by the Beech-Nut Company’s campaign to sell overstocked bacon. In the 1920s, they enlisted the marketing firm of Edwards Bernays to help. Bernays – a former wartime propagandist, University professor, and creator of the first marketing firm in the US – knew that the general public trusted their doctor for diet-related advice. Bernays asked his marketing agency’s on-staff corporate doctor “if a larger meal in the morning would be better for people’s health”. The doctor agreed, as it seems logical that “more energy at the start of the day is a good thing”. Bernays then had that doctor write to 5,000 of his closest doctor friends asking if they also agreed, and more than 4,500 wrote back saying they did. “4,500 physicians urge Americans to eat heavy breakfasts to improve their health” is a compelling story and was published in newspapers along with ads for Beech-Nut Bacon. The casual opinion of 4,500 doctors was essentially masked as peer-reviewed research, and 100 years later, bacon is still a staple at breakfast tables across America.1

Personally, I’ve worked as a developer and in other hands-on technical roles. I’ve also worked in adjacent roles such as developer relations, sales engineering, and consulting. One of my biggest career takeaways has been the power of marketing, which is part of what inspired me to research its history and write this series. I hope this series showcases an appreciation for technical education and ethical marketing, while shining a spotlight on unethical indoctrination masquerading as instruction for the propaganda that it is.

Modern technical propaganda and why we should care

In my current role managing an open source program office (OSPO), I’ve seen a rise in benchmarketing and the divisive open source politics that emerges from it. “Benchmarketing” is the marketing practice of highlighting specific performance benchmarks to showcase a product favorably, often by focusing excessively on positive data points while ignoring or omitting less favorable ones. When the distortion of facts becomes extreme and intentional, benchmarketing fits the definition of propaganda.

While tech-savvy developers and other technologists might quickly recognize practices like “benchmarketing”, what happens when the underlying technologies eventually become very difficult to understand?

We will witness this with the rise of AI and quantum. As technology continues to advance, and the gap between surface knowledge and deep knowledge of very complex topics widens, the distinction between instruction and indoctrination may become even more nuanced and hard to recognize. This has the power to cause untold damage, like discouraging an entire generation of students from pursuing computer science for fear of AI making computer science obsolete. When this narrative is pushed using unethical tactics by corporate interests for influence and monetary gain, it’s propaganda.

If we’re not willing to push back on simple propaganda like benchmarketing, how will we respond to more complex forms of technical manipulation that may have a profound impact on our profession and on society?

The influence of propaganda on open source

Benchmarketing is not the only form of modern technical propaganda. Growing economic pressures may drive more Commercial Open Source Software (COSS) companies to adopt source-available licenses with restrictive clauses, straying from true open source principles, while attempting to continue to benefit from the positive public relations of being perceived as a supporter of Free and Open Source Software (FOSS). If you would like to understand how to destroy open source with fauxpen license shifting, read about the recent wave of these license shifts and how the concept of “fauxpen” emerged.

Fauxpen – or false open – happens when companies place themselves in the position of supporting open source only for the public relations benefits, while harming open source in private. Fauxpen license shifting tends to be the most visible action when a company walks a tightrope between open source ideals and the drive for profits above all else. Open source support is best represented through actions, like funding a project and choosing an open source license for that project, not press releases that claim support for open source while moving away from the very principles that open source is built upon. I hope that by discussing these trends we can shine a spotlight on what we are willing to accept as an open source community.

If you’re only interested in modern technical marketing anti-patterns, you can visit the above links and stop there. But if you’re interested to learn how these topics are part of a larger discussion on propaganda, continue reading to learn about the first technical propaganda battle in corporate history – the “electric current wars” of the late 1800s.

The first technical propaganda battle in history

The electric current wars was a fierce battle between the Edison General Electric Company and the Westinghouse Electric Corporation to standardize the American power grid. To do this, they first needed to gain broad public support for one or the other of their competing technologies – direct current (DC) or alternating current (AC), respectively.

This story illustrates how fierce competition between rivals to dominate a technical market can bring out the best and worst sides of marketing and public relations. When advanced technology – too complex for the general public of a particular era to comprehend – is marketed by rational manipulators with a questionable moral compass, it isn’t long before instruction gives way to indoctrination. It wasn’t long ago that the public electrocution of animals was considered part of a valid public relations campaign to demonstrate a new technology and discredit a competing technology.

Exploring how Westinghouse created the first public relations team to refute propaganda from the Edison General Electric Company during the electric current wars can shed some light on the positive aspects of public relations, and serve as inspiration on how we can refute technical propaganda in a modern context. Not only did the Westinghouse public relations team put an end to some of the worst corporate propaganda in history, but they were effective from a revenue perspective as well, helping Westinghouse to win the electric current wars by winning the contract to provide power to Buffalo, New York in 1896. The Westinghouse PR team helped to make Buffalo the first city in history completely electrified with alternating current.

Public relations as an academic subject

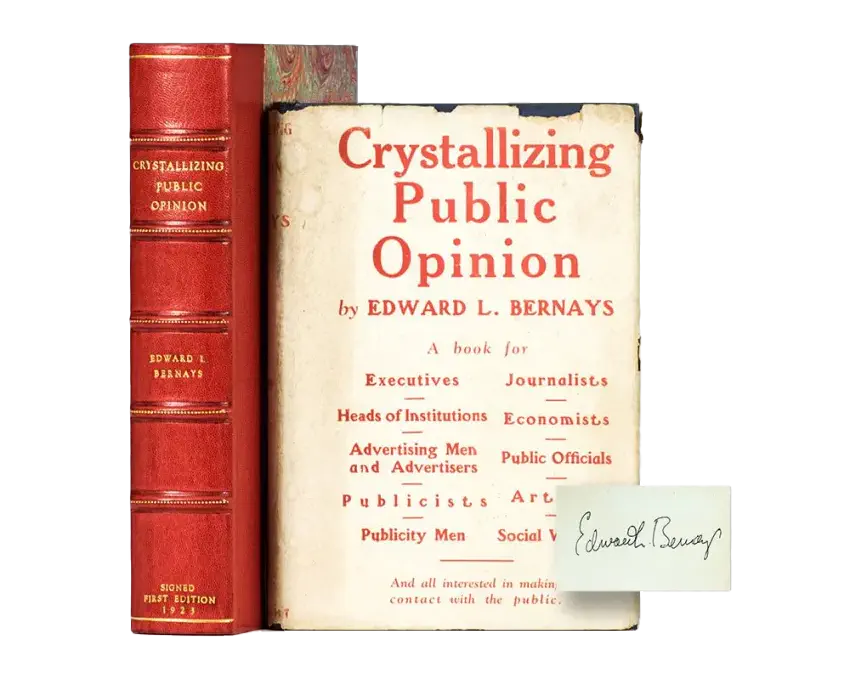

Public relations is a sophisticated field of study that has been taught in universities since the 1920s, after Edward Bernays wrote the first academic textbook on the field of public relations called Crystallizing Public Opinion (1923), and taught the first class on public relations at New York University (NYU) the same year. It’s through this formal study that the concepts of “rational manipulation” and “engineered consent” emerged – tactics that have been used in business for over 100 years, tactics that have been designed and studied from the beginning of marketing and public relations as professions. We can see their effect on a range of topics, from the public acceptance of smoking, to popular opinion that a nutritious breakfast is made up of bacon and eggs.

The evolution of public relations and psychoanalysis illustrates how the history of marketing has shaped every facet of our modern lives from what kinds of cars we drive, to our preference for certain fashion labels, and even the types of developer tools we use. It’s also why we can’t decouple marketing anti-patterns from the origins of marketing, and the origins of marketing from the origins of propaganda.

Edward Bernays was a US government propagandist for the Committee on Public Information (CPI) during World War I right before he wrote the first academic textbook on public relations. He is also the nephew of Sigmund Freud, and was heavily influenced by Freudian psychology, which influenced his academic and professional works in propaganda, public relations, and marketing. Bernays worked at the CPI alongside another influential propagandist, Ivy Lee, the first public relations executive in corporate history for the Pennsylvania Railroad Company. It was Lee who wrote the first job description for a VP-level public relations executive.

However, propaganda dates back much before the early 1900s, all the way back to the invention of the printing press.

The origins of propaganda

The origin story of propaganda explores the early concepts of formal propaganda, by briefly exploring the works of the Propagation of the Faith (Congregatio de propaganda fide), established in the early 1600s to help propagate Catholicism. Understanding this office and their work can shed light on the literal meaning of propaganda as it first originated and then changed over the centuries.

The desire for small groups to gain wide influence within a literate society is not a new concept, and will not cease because the terminology is uncomfortable to discuss. The concept of propaganda and its evolution into public relations has evolved and adapted to the changing landscape of communication technologies and societal norms, even changing its own definition along the way.

Understanding propaganda through a historical lens is as crucial as understanding it through a modern lens, even in areas we’re already familiar with. By understanding its origins and purpose, we can more quickly spot its application today, and thereby reduce its effectiveness.

Continue reading

Understanding the history of a profession I thought I knew has been enlightening. I now have even more respect for the ethical marketing I come across from genuine open source advocates, and the genuine marketers I’ve worked with in the past.

It’s far more difficult to produce ethical, high-quality education than it is to spam FOSS with low quality indoctrination masquerading as instruction. Let’s reward the COSS companies helping to educate us, and disincentivize the COSS companies trying to indoctrinate us.

If you would like to dive deeper into this fascinating subject, let’s explore the origins of propaganda in a technical marketing context by discussing the electric current wars of the late 1800s. This was the first technical propaganda battle in corporate history, and what inspired the creation of the first public relations team.

Next (part 2 of 7): The original format wars