The original format wars

Series: The history of modern technical propaganda

25th of February, 2024

Imagine you’ve quit your job and poured your life savings into creating a revolutionary new tech product. You’re ready for production, but there’s a small detail that needs sorting out.

Like any good tech innovator, you haven’t even thought about sales and marketing yet. That’s how everyone knows you’re the real deal. Research and development was the hard part – so now that the product is ready and technically superior to everything else, selling it should be a walk in the park. Hand-waving won’t cut it anymore though, we need a concrete strategy. As a fellow technologist, how would I recommend that you position your new product for world domination?

My instinctive approach might be to position all of the product’s innovative features as the core reason that prospective consumers should evaluate and buy the product. If I’m feeling especially confident, I may even position the feature sheet of the product against comparable features of competing products. The summary of our product’s technical merits will be so thorough and accurate that the market will weep with joy and awe. Come to think of it, all of this marketing is a waste of time. Prospective customers are bound to discover it through word of mouth alone; doesn’t the technically superior product always come to dominate the market?

Let’s discuss one example: the videotape format wars of the 80s. Some posit that VHS defeated Betamax in the videotape format wars because of the ubiquity of pornographic material on VHS, combined with the relative affordability of VHS players compared with Betamax players. Sony lost the videotape format wars, and JVC won, even though Sony’s Betamax technology was superior. Oops.1

How did this upset happen?

Sony’s marketing dollars focused on the technical superiority of Betamax, while JVC promoted the relatively affordable price of VHS, plus the high availability of players for rent in video stores on launch. Even Beta’s product manual (1981) was beautiful in a way that was ahead of its time.2 The features that JVC did promote were of particular importance to mainstream adopters, like a much longer recording time on blank VHS tapes. The attractive price and availability of players incentivized producers to publish a wider range of movies on VHS, including 🌽. This became a positive feedback loop. More VHS players in circulation resulted in more movies released on VHS, until finally VHS tapes dominated the video stores of the 80s and Betamax died off. JVC wound up dominating the home videotape market for many decades to follow.3

This is proof that features alone don’t sell products. Before simply assuming that the technical superiority of a product has a direct impact on the market dominance of that product within its category, let’s ask a few questions first:

- Can we prove that the superior technical features or specs of a product/service persuades adoption/purchase decisions enough to dominate a market?

- If not, what actually does?

Marketing teams have been helping to answer these questions and sell technical products for over a century. To fully understand the role of marketing in a modern technical landscape, let’s first explore how marketing as a profession began. This will help us to understand the entire spectrum of marketing, from best practices to outright disinformation. This historical context will help us to better understand the types of marketing we’re seeing in a modern tech landscape.

Let’s travel back in time to the 1800s, slightly before the first public relations team was created. The era of carnivals and snake oil and cocaine in your Coke. There was an emerging technical revolution happening so profound that it may as well have been magic to the general public. The innovation was electricity, and this technological marvel was driving the need for a more sophisticated approach to influencing public opinion.

The original format wars (“the current wars”)

Well before the videotape format wars of the 70s and 80s were the electrical current wars of the late 1800s. A technical propaganda battle was brewing between the Continental Edison Company, which owned the patent for direct current (DC) electricity, and the Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company, which licensed patents to alternating current (AC) electricity technology from a number of inventors and companies, including the Tesla Electric Company. The stakes were tremendous: a new standardization of the American power grid, which was still largely in the private domain.4

Thomas Edison originally developed direct current (DC) electricity, which was the standard in the late 1800s. However, it’s important to remember that entire cities were not yet electrified. The issue is that DC voltage cannot be effectively changed, meaning that high voltage direct current at the street level (e.g, 500 volts) cannot branch out and step down for use in individual homes (e.g, 120 volts). This was a major blocker for the emerging power utility industry.

A young engineer named Nikola Tesla happened to begin a new role at one of Edison’s companies, Société Electrique Edison, in the 1880s. In many ways, he was the true definition of a Site Reliability Engineer: a core part of his early role with Edison in Europe was to travel across France and Germany to troubleshoot engineering problems at newly constructed Edison generator installations. These were used extensively in many domains, such as powering early streetcars. His knowledge, talent, and promise quickly caught the attention of Charles Batchelor, Thomas Edison’s close confidant and advisor. Batchelor arranged the transfer of Tesla to another of Edison’s companies, Edison Machine Works in the US, where he could fully leverage his research and development talents.5

It’s at Société Electrique Edison where Tesla gained significant and practical R&D experience; a core part of his new role was designing and building improved versions of direct current dynamos and generators. His work with Edison’s companies lasted for a few years in total, and then in 1885 he penned an essay, “Good by to the Edison Machine Works”, and struck out on his own.6

In the meantime, researchers had long been researching and developing alternating current (AC) as a competing technology to direct current (DC). They believed this to be the superior technology for transmitting power for two core reasons:

- It was easier to transmit AC over longer distances, and

- It was easier to convert AC from higher or lower voltages.

By comparison, DC has some notable shortcomings for current transmission:

- DC systems were more expensive to install,

- DC voltage is not easy to change, and

- DC cannot be transmitted economically over longer distances.

Tesla certainly didn’t commercialize AC on his own, and stories of Tesla as the inventor of AC are simply works of fiction.7 AC technology had been under development since the 1830s, and as a matter of fact, Tesla studied AC in university. He certainly played a role in the evolution of AC technology, but was not the lone inventor of alternating current. What actually made AC commercially reasonable were two notable transformer designs from Europe: Gualard-Gibbs transformers, from French and Italian inventors Lucien Gaulard and Galileo Ferraris, and “ZBD” transformers, from the Hungarian research team of Károly Zipernowsky, Ottó Bláthy, and Miksa Déri.8

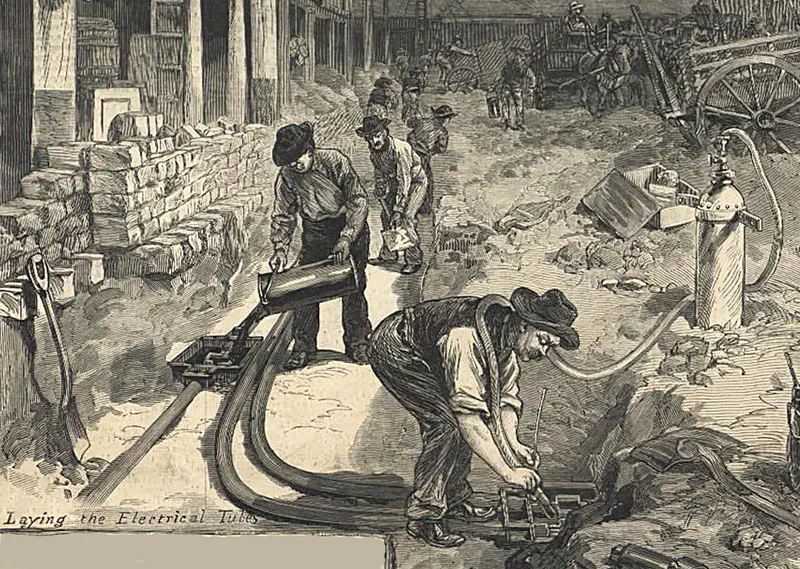

While European researchers were innovating and perfecting AC technologies, back in America, Americans were Americaning by innovating on the business side of this technical epoch. The Westinghouse Electric Company was formed in 1886, and quickly began purchasing the patents for both Gualard-Gibbs and ZBD transformer designs, along with the patent for Siemens AC generators, and a whole basket of other related AC technology patents. This put Westinghouse in a position to roll out the pilot of a complete AC system, which was designed to light up a small row of businesses in Great Barrington, Massachusetts.9

The Westinghouse pilot was a success, and proved some notable advantages of AC over DC in a real-world environment. Notable findings include the lack of power loss over the initial 4,000 foot distance between the businesses, along with the ability to step down 500 AC volts at street level to 100 AC volts in each store to power incandescent lamps. Westinghouse was entering the platform business, determined to standardize the entire American electrical grid.

In the same year, Tesla was continuing to innovate in business and technology. While he continued his technical research on AC, he also formed a professional relationship with two future business partners: Alfred S. Brown, a Western Union superintendent, and Charles Fletcher, an attorney from New York. Both men were experienced in the creation of companies, and Tesla was now considered a brilliant engineer and inventor. Based on the underpinnings of Tesla’s technical ideas, the three formed the Tesla Electric Company in 1887, with the profits to be split three ways between the founders. The plan from the beginning was for Tesla to develop new technologies, while Brown and Fletcher focused on publicity and patents. After a successful tech demo of Telsa’s AC motor at the American Institute for Electrical Engineers in 1888, engineers from the Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company eventually licensed the patent for Tesla’s poly-phase AC induction motor for a rate based on the horsepower generated by installed motors – $2.50 USD per AC horsepower produced. Westinghouse also hired Tesla as a consultant at a rate of $2,000 USD per month.

Edison’s electrocution spectacle

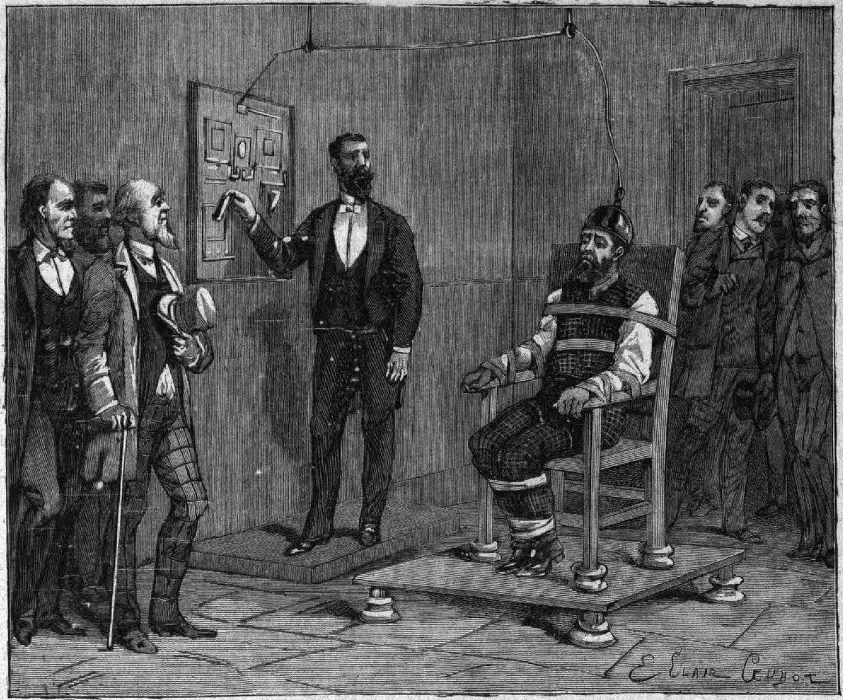

From here on out, let’s focus on the actions of the Continental Edison Company (“the Edison Company”), and the Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company (“the Westinghouse Company”). We’re not talking about the men specifically: Thomas Edison, George Westinghouse, and Nikola Tesla. From all accounts, the stories of a vicious personal feud between any of the men are disputed. However, the battles were certainly waged between their respective companies, the most notably being the Edison Company’s depraved public relations campaign, which involved the electrocutions of animals and criminals using AC to stoke the fears of the public against alternating current.

You read that right – sensing Edison’s losing hand in the competition, the Edison Company began a relentless propaganda campaign of disinformation, half-truths, and lies. The campaign devolved into spectacle, culminating with the public electrocutions of stray animals and criminals with alternating current to manipulate popular opinion into believing that AC was dangerous, and DC was the safer technology. The Edison Company even made short films of these “demonstrations”.

Some publications I’ve come across attribute this cruelty to Thomas Edison personally, but those accounts appear to be highly questionable. Proving or disproving Thomas Edison’s direct involvement is not the core of the argument. However, there’s no denying that the Edison Company engineered this unethical propaganda campaign.

When this public relations campaign wrapped up, by some estimates, 1,200 such electrocution events were conducted and filmed on what might be described as a “propaganda roadshow”. This included the famous electrocution of Topsy the elephant, one of the most controversial acts of public spectacle in an era when public spectacle knew very little boundaries.10

AC electricity can cause harm. All electricity can cause harm when intentionally used to cause harm. By putting on such a display to stoke the fears of a public by manipulating their emotions – a public that didn’t yet comprehend the science of electricity – the Edison Company twisted the narrative towards their desired outcome: AC is dangerous and DC is safe. This became an accepted fact for a period of time until the Westinghouse Company fought back.

Continue reading

The need to influence large groups of people was not a new problem, and not limited to the selling of products and services. There are many ways to gain influence, from the most benevolent, education, to the most sinister, force.

The story of the electric current wars depends on a unique type of influence with the goal of gaining broad public support, based on the right combination of intellectualism and emotional manipulation. A type of influence that requires the veneer of education, but with goal of indoctrination by any intellectual means necessary.

This series will explore this type of influence that blossomed with the formation of a literate society and the printing press, propaganda. To explore the origins of propaganda, we’ll need to travel back in time to the 1600s. Only then can we finish the story of the electrical current wars and connect all of this to the modern technology landscape.

Next (part 3 of 7): The origin story of propaganda