The lone hacker myth is just that, a myth. The real revolution in software has been the messy, political, collaborative world of open source. It was sparked by a few visionaries, and then cultivated by thousands of minds scattered across time zones and terminals, wiring together something bigger than themselves.

Open source is power. It took an impossible idea, pooling “spare” developer talent, to build software that no single person or company could ever truly own, and no single company could ever afford to incubate. Free and Open Source Software (FOSS) might be the closest humans have come to functional digital communism.

What sparked it all? Linux arrived in 1991 under a license that didn’t quite fit its spirit. By 1992, it had shifted to the GNU General Public License (GPL), unleashing collaboration on a scale even its creator hadn’t imagined. The GPL drew a line in the sand, codifying an ethos of communal innovation into a legal framework of licenses and copyrights that guaranteed the right to use, modify, and share.

Software by the people, for the people.

In 2018, a new pattern emerged.

Companies that had thrived on the backs of open source contributions began shifting their licensing models, moving from open to restricted in subtle but deliberate ways. They called it source available. They called it free and open. But to many developers, it was fauxpen, fake open source, a betrayal of the very ethos that made open source a force in the first place.

This was a structural shift, driven by the pressure of venture-backed growth and the tightening noose of competition. It struck at the core of the social contract that made innovation possible.

Let’s explore the origins of open source, the foundations that help to govern and steer it, the threats it faces today, and a future where it serves its original spirit while providing a path for contributors to make a living.

The Rise of Open Source

The GNU General Public License (GPL), created in 1989 as part of the GNU Project, promoted the free use, modification, and distribution of software. It transformed a DIY ethos into a legally protected movement, ensuring developers’ rights and freedoms at a global scale.

In 1991, Linux launched under a license that restricted commercial redistribution. By 1992, it shifted to the GPL, aligning with Linus Torvalds’ vision of a collaborative and open development model.

This shift unlocked a wave of contributions, supported by the broader GNU ecosystem, including essential tools like GCC. Even today’s tools, such as Git, trace their roots to these principles. This shows that license choices are not just “boring technicalities”, but geninuely shape the nature of long-term innovation.

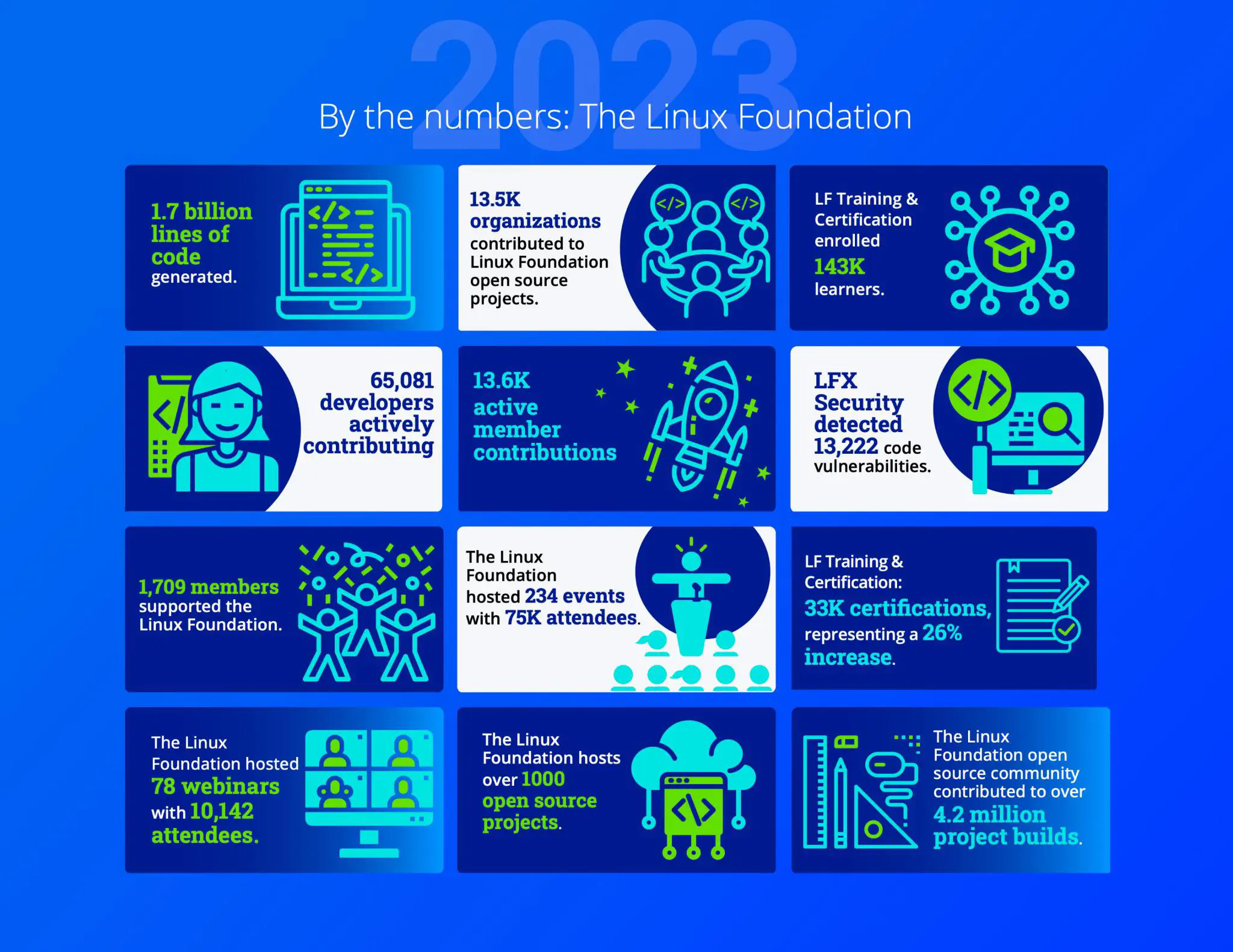

Fast forward to today, and Linux powers everything from web servers and supercomputers to smartphones and embedded devices. It runs ~96% of the top one million web servers1, forms the backbone of countless enterprise systems2, and supports a massive ecosystem of digital infrastructure.

Imagine the cost of building a project like Linux within a closed-source, proprietary model? Even if a single company funded such an undertaking, the result would be trash quality and way less impactful. Consider how many success stories open source has made possible, and how many startup founders built fortunes on foundations planted by early pioneers. Yet wealth generation was never the heart of the open source movement. Quite the opposite and quite the paradox.

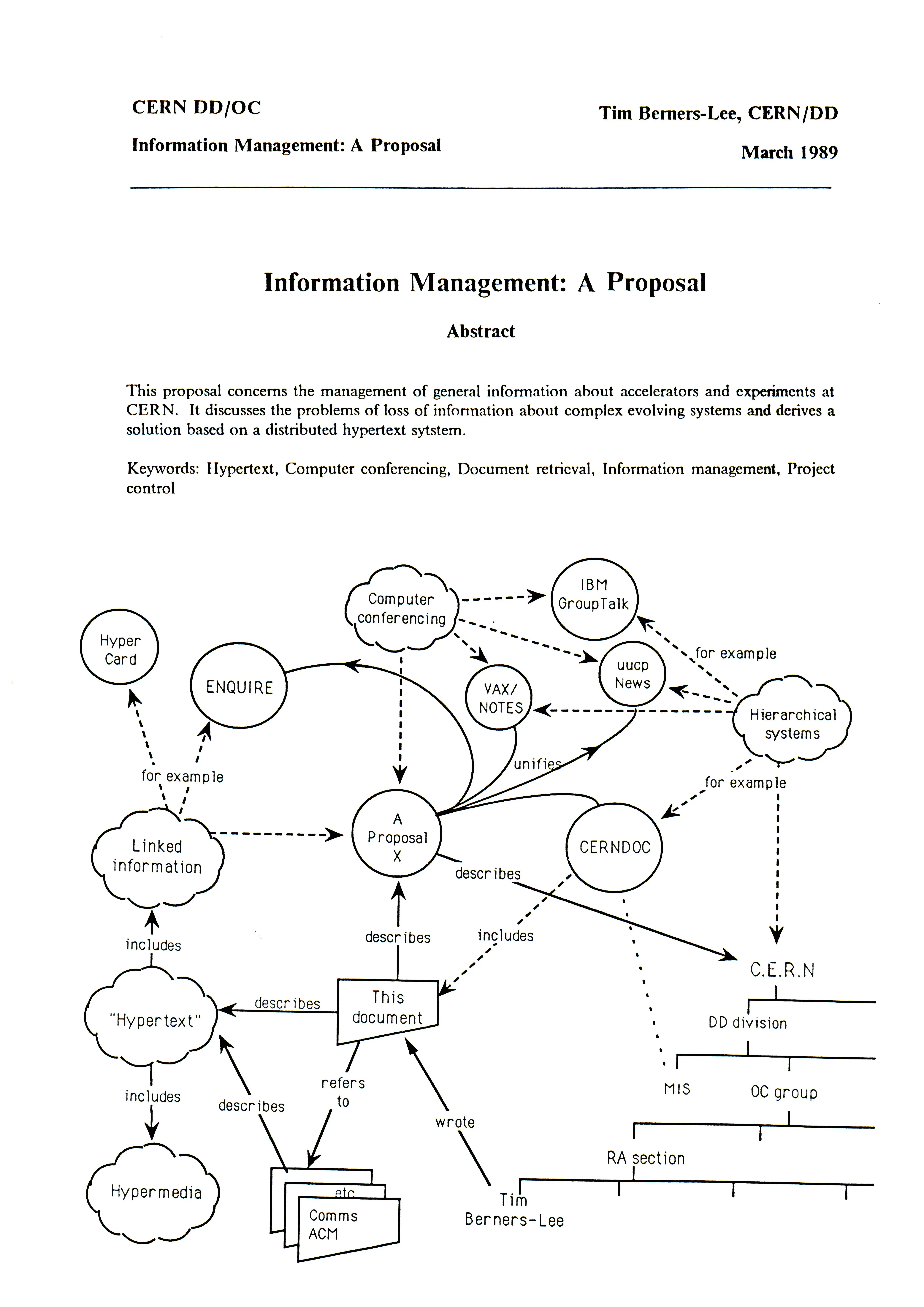

But what about the internet itself? Any complete discussion of open source must also include the contributions of Tim Berners-Lee, whose work extended its influence far beyond GNU, GPL, and Linux. Berners-Lee invented core web technologies like URL, HTML, HTTP, and the first website, laying the groundwork for the World Wide Web as we know it. These foundational protocols were released freely to the world, ensuring that the web would remain an open and accessible platform for innovation and communication.

He also ensured his ideas were freely available with no patents or royalties. In 1994, Tim founded the W3C to advocate for open web standards and ensure they remained royalty-free. His commitment to open standards, along with his stance on net neutrality as a human right, embodies the ethos of open software for the public good. This combination of technical innovation and dedication to human progress is the true essence of “free and open”, though you will hear this term again in a very different context.

Licensing Versus Copyright

To understand why certain license shifts feel like a betrayal, we need to look at copyright. By default, code you write in your free time (outside of employment) remains your intellectual property, even if it’s merged into an open source project. Contributor License Agreements (CLAs) formalize agreements between contributors and project owners, often transferring full ownership of the contributed code. The owner could be an individual, a company, or a foundation.

There are two typical scenarios:

- Projects governed by commercial open source software (COSS) companies, where CLAs transfer copyright to a for-profit entity.

- Projects governed by foundations like Apache, where CLAs transfer copyright to a nonprofit steward.

The copyright holder can re-license contributions covered by a CLA. This is why license choice matters. It signals to contributors that their work will either remain part of the open commons or be used in a way consistent with FOSS values, even if they no longer hold the copyright.

One of the most important decisions for contributors is to support projects that embrace true open source principles. These principles are best represented by open source licenses. But who determines what “open source” really means?

The Open Source Initiative (OSI) and Open Source Definition (OSD)

The Open Source Initiative (OSI), founded in 1998 by Eric Raymond and Bruce Perens, advocates for open source software and helps the corporate world understand and adopt its principles. The OSI created and maintains the Open Source Definition (OSD), a set of criteria that licenses must meet to be considered truly open source.

The OSI formalizes governance around what “open source” means. It reviews new licenses to ensure they comply with the OSD, establishing consistent standards for freedom and openness. This clarity builds trust among developers and organizations and prevents companies from mislabeling software as “open source” when it does not meet the definition.

The OSI supports open source by:

- Providing and maintaining a clear definition of open source.

- Standardizing how open source licenses are evaluated.

- Ensuring consistent and accurate use of the term “open source” within the software industry.

Let’s step through each of these in a little more detail.

The OSI’s formal review process ensures that new licenses claiming to be “open source” align with the OSD.3 Only licenses that meet the OSD’s criteria, especially the core principle of protecting software freedom for users and developers, receive OSI approval. This certification process fosters trust and legal clarity, making it easier for individuals and organizations to adopt and contribute to open source projects confidently. The OSI Board of Directors also advocates for proper use of the term “open source,” especially by COSS companies.4

The Rise of Fauxpen

In the 2010s, the Business Source License (BSL) emerged, a commercial, proprietary license that mimicked open source but withheld its core freedoms. Notably, the BSL prohibits licensed code from being used in production without explicit approval from the licensor.5

Why did the BSL emerge in the first place?

During the 2010s, venture capital, fueled by low interest rates, flooded into commercial open source software (COSS) companies. Some of these companies enriched the FOSS ecosystem while building profitable businesses. Others, under the strain of scaling and competitive pressures, began to stray from open source values.

Enter fauxpen. Fauxpen is not just a debate about licenses. It describes a company’s strategic shift from genuine open source principles to a model that maintains the appearance of openness while pursuing commercial gain. It happens when companies once committed to open source distance themselves from its principles but continue to market themselves as champions of the cause. This creates a complex form of technical propaganda, balancing a public facade of open advocacy with private, profit-driven actions.

The fauxpen playbook often follows this pattern:

- The company distances itself from open source licenses it once embraced.

- It adopts restrictive proprietary licenses to limit competition or reduce user freedoms.

- It launches a public relations campaign framing itself as a champion of open source, despite the shift.

The first two actions may be valid business strategies in a competitive market. COSS companies do not owe the community free software, just as developers do not owe their labor to for-profit businesses. Using copyright law to protect competitive advantages is a legitimate tactic, but it often alienates the developer community.

What defines fauxpen is not just the license shift but the combination of behind-the-scenes actions that betray open source values and the public relations spin that tries to mask them. A license shift alone may not be fauxpen. But when paired with misleading narratives, it becomes something more insidious.

This rest of this essay focuses on that third element, the PR and narrative tactics that define fauxpen, and how they impact both open source communities and contributors.

How Did We Get Here?

Let’s walk through a condensed timeline of fauxpen. While there are other examples of fauxpen, these key events outline the pattern.

2013: MariaDB and the Business Source License (BSL)

The BSL, introduced by MariaDB Corporation and proposed by MySQL’s original developer, was a hybrid model combining elements of proprietary and open source licenses. It temporarily restricted certain commercial uses, aiming to sustain projects financially while eventually transitioning back to open source under the GPL.

Though controversial, the BSL was upfront about its purpose. It didn’t masquerade as open source and even saw refinement through engagement with the OSI. Bruce Perens, OSI co-founder, even helped MariaDB address concerns reflecting a collaborative approach with the FOSS community.6

But unfortunately, the BSL served as a warning, foreshadowing the tensions between open collaboration and financial sustainability.

2018: MongoDB and the Server Side Public License (SSPL)

MongoDB’s introduction of the SSPL marked a sharp turn. Unlike the BSL, which eventually reverts to open source, the SSPL included a clause requiring service providers to open source their entire service infrastructure if offering MongoDB as a managed service.

Percona called the SSPL “anaconda-like.”7 The license’s aggressive stance sparked a domino effect, with other vendors adopting similar strategies. This is the license shift that truly entrenched fauxpen practices, prioritizing competitive advantage over open collaboration. The SSPL effectively locked out competition.8

2021: Elastic and the Elastic License (ELv2)

Elastic’s decision to shift Elasticsearch from Apache 2.0 to a mix of SSPL-1.0 and ELv2 was framed as a defensive move against Amazon’s Open Distro for Elasticsearch. However, it also reflected a pivot from open source to a more controlled commercial model.9

Elastic’s marketing continued to label Elasticsearch as “free and open”, despite significant restrictions. This rhetorical shift blurred the lines between “source available” and genuine open source, further muddling trust in FOSS principles.10

Meanwhile, Amazon’s fork, OpenSearch, retained its Apache 2.0 license and gained momentum. By late 2023, OpenSearch formalized governance to safeguard its open source future.11

“Elastic’s relicensing is not evidence of any failure of the open source licensing model or a gap in open source licenses. It is simply that Elastic’s current business model is inconsistent with what open source licenses are designed to do. Its current business desires are what proprietary licenses (which includes source available) are designed for.” — The OSI Board of Directors

Adopting a restrictive license may make business sense, but continuing to market the result as open source erodes trust. Fauxpen emerges not just from license changes, but from the gap between stated principles and actual practices.

The Open Source Initiative Pushes Back

The Open Source Initiative (OSI) has taken a strong stance against fauxpen license shifts.

“We’ve seen that several companies have abandoned their original dedication to the open source community by switching their core products from an open source license, one approved by the Open Source Initiative, to a ‘fauxpen’ source license. The hallmark of a fauxpen source license is that those who made the switch claim that their product continues to remain ‘open’ under the new license, but the new license actually has taken away user rights.” — OSI Board of Directors12

When a corporation shifts its software to a proprietary license that lacks OSI approval but continues to label it as open source, it undermines the foundation of open source.

“Proprietary software masquerading as open source – what has been termed fauxpen source – is toxic. It’s an intentionally deceptive hybrid that seeks to give its proponents the best of both worlds: the positive vibe and broad distribution of open source, together with the commercial leverage of proprietary software.” — Donald Fischer, Fauxpen Source is Bad for Business13

Some vendors, recognizing the controversy, have stopped calling their products “open source” altogether. Elastic, for instance, rebranded Elasticsearch and Kibana as “free and open” after switching from Apache 2.0 to either SSPL-1.0 or ELv2, two flavours of business source licenses. But this shift didn’t quell the fauxpen debate. In fact, it deepened it. The phrase “free and open” sounds even more permissive than “open source,” and dangerously close to “free and open source software” (FOSS). SSPL-1.0 and ELv2 include significant commercial restrictions, especially designed to limit competition from other service providers, which contradict the ethos of FOSS.10

This type of wordplay lies at the heart of the fauxpen debate, where the line between marketing spin and outright propaganda becomes increasingly blurred.

A company’s genuine commitment to open source is reflected directly in its license choices. Licenses such as Apache-2.0, GPL-2.0, BSD-3-Clause, and LGPL-2.1 – all approved by the OSI – represent that commitment. Combining these with ethical use of Contributor License Agreements (CLAs) sends a clear signal of support for the open source community.

Where Does FOSS and Fauxpen Go From Here?

In my view, license shifts should be approached with understanding before jumping to conclusions. Behind every project is a team of developers, many of whom may have little to do with decisions about licensing. While fauxpen license changes are relatively rare, some transitions to non-fauxpen BSL models may be essential for a project’s survival. It is reasonable for companies profiting from open source to contribute back to maintainers. This approach doesn’t undermine open source ideals… unless it falsely claims to adhere to them while doing the opposite.

The real challenge arises when a project unexpectedly changes its license after years of accepting contributions. For some projects with minimal volunteer input, such a shift might be an existential necessity. However, when community contributions are significant, this can feel like a betrayal, and the community may need to step up. Community members can always fork the last open source version, preserving its legacy and principles independent of corporate interests.

If you take one thing from this essay, let it be the importance of vigilance when it comes to Contributor License Agreements (CLAs). Open source contributors should be fully aware of where their efforts are going and who ultimately benefits from their volunteer time and energy. Projects stewarded by foundations committed to open source values are (in my opinion) more reliable and worth long-term support compared to projects likely to shift toward proprietary models, especially in light of recent fauxpen moves.

I’m not arguing against contributing to commercial projects. I’m saying this: invest your time wisely. Prioritize projects that align with open source principles and contribute positively to the community. Otherwise, spend your time on other things, like hobbies, family, or friends. Don’t let your free time subsidize well-funded COSS companies.

Summary

Fauxpen isn’t a single action. It represents a fundamental shift in a company’s approach to open source. A license change is often just the beginning, with companies that once embraced FOSS becoming increasingly competitive with it after the shift.

So, how should we respond to the rise of faux open source software?

Focus on innovation, and steer clear of PR battles. I hope that a key takeaway from this essay is the importance of prioritizing technological progress over engaging in conflicts with well-funded COSS entities. Our collective goal should be to preserve the integrity and enthusiasm of the open source community, not to get bogged down by endless marketing spin. Fortunately, technical leaders and decision-makers are increasingly able to recognize fauxpen for what it is. Over time, innovation wins out over posturing, so let’s conserve our energy for what truly matters.

In the end, we must stay vigilant about the CLAs we sign, the projects we contribute to, and the technologies we advocate for when making adoption decisions. That’s how FOSS continues to stand for real freedom and community, not just endless marketing propaganda.